Christina Thompson’s book Sea People: The Puzzle of Polynesia, amazed me for two reasons—first, that she was able to pull together centuries of written and oral records on the vast subject of Polynesian history and, second, that her book, despite its scholarly approach, is just plain entertaining. In fact, I couldn’t put it down.

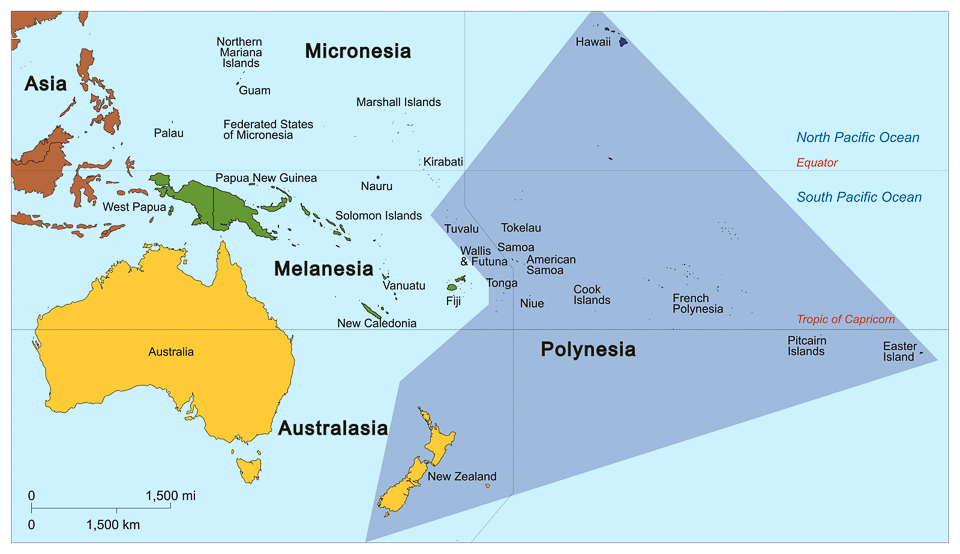

Thompson addresses a question that has baffled mankind for centuries: How did one group of people – related ethnically, culturally and linguistically—manage to colonize islands scattered over the vast Pacific Ocean—an area that covers 10 million square miles. This is “the problem of Polynesian origins,” and Thompson calls it one of the great geographical mysteries of mankind. In her own words:

“They had no knowledge of writing or metal tools—no maps or compasses—and yet they succeeded in colonizing the largest ocean on the planet, occupying every habitable rock between New Guinea and the Galapagos and establishing what was, until the modern era, the largest single culture area in the world.”

Thompson’s subject is, arguably, as vast as all of Polynesia. And she makes no pretension that she can definitively answer the question of when, how, or why the Polynesians colonized the Pacific islands. Still, her contribution is immense: She has pulled together 300 years of Western scholarship and science, as well as the oral histories and mythologies of the Polynesians themselves.

In seeking answers, Thompson draws on sources that range from journals of the earliest explorers to scholarship that dates from the 17th century to the present. She references the works of experts in many fields—anthropology, mythology, archeology, biology, navigation, radiocarbon dating, DNA analysis and more. She also records many “stumbles” along the way—the faulty theories of early anthropologists, the inconsistencies of early radio-carbon dating, the limits of DNA analysis. The list goes on.

The book starts out with gripping tales of encounters between the early European explorers and islanders. We read about Alvaro de Mendaña, the first to discover the Marquesas Islands in what is now French Polynesia (1595), Abel Tasman in New Zealand (1642) Samuel Wallis’ discovery of Tahiti (1767) and James Cook’s multi-year voyages through the Society Islands, New Zealand and Hawai’i. Wallis’ reception in Tahiti mimics many others: Polynesians paddle their canoes out to welcome the English with fruit and provisions. All goes well until a mischievous native makes a threatening move, at which point the Europeans open fire. At that point, the Polynesians speed back to shore only to return in a frenzied assault of stones and spears.

In the case of Captain Wallis, the situation calmed down, and soon the sailors aboard Wallis’ ship, the Dolphin, were bartering for goods and services. But what the men wanted most was to consort with the beautiful Polynesian women. As a result, “sex for nails” became a popular trade. [The Polynesians, with no metal-working skills, must have realized the value of nails.] In fact, so high was the demand that, Thompson relates, “Within a matter of weeks … every cleat in the Dolphin had been drawn, and the carpenter was saying to anyone who would listen that he feared for the integrity of the ship.”

Over the years, the European footprint in the Polynesia Triangle increased. The islands became stop overs for the hugely successful whaling industry in the early 19th century, resulting in a plethora of local support industries. Sadly, however, European diseases nearly decimated the population. (The population of the Marquesas, we learn, dropped from an estimated 50,000 before Europeans arrived to a little over 2000 in 1926.)

Solving the Puzzle

In the latter two-thirds of the book Thompson introduces us to the scores of people who have attempted to solve the question of Polynesian origins over the centuries. First, there was Captain Cook, who in the late 18th century noted the similarities of culture, body type and language among the Pacific Islanders. Then there was Abraham Fornander, a Swede who, having settled in Hawai’i, wrote a lengthy history based on “genealogies, customs, legends, place names, numerals and mythological traditions” across the Pacific. Another chapter is devoted to Te Rangi Hiroa, a preeminent 20th century anthropologist from New Zealand, who was half Māori and half Anglo-Irish.

But Thompson doesn’t stop there. Other chapters cover linguistics, traditional Polynesian navigation, anthropology (including the study of body types), as well as archeology and DNA studies. There’re even chapters on modern-day attempts to sail the Pacific using crafts of yesteryear—for example, Ben Finney’s double-hulled voyaging canoe, the Hōkūl’e, which sailed from Hawai’I to Tahiti in 1976 and Thor Heyerdahl’s balsa wood raft, which set out from Callao, Peru, in 1947 to prove his theory that Easter Islanders could have originated in South America.

In the end, there is strong archeological and DNA evidence suggests that the Polynesians originated somewhere in Asia (probably Taiwan), stepping their way across Melanesia, then on to Samoa and Tonga, before spreading out over the Pacific Triangle. The latter part of the journey, risking everything and sailing against the trade winds, is simply mind-boggling. And although Thompson sets forth timelines for movements, she doesn’t answer the fundamental question: Why did the Polynesian’s ancestors sail into the Pacific with no idea of what might lie ahead? Were they forced out of Melanesia by established tribes? Did climate change make it easier for them to sail east in certain years? Or were these men and women attempting to achieve the mythical hero status of their sea-faring ancestors?

In the end, Thompson admits the mystery of the “puzzle of Polynesia” is not likely to be unraveled. Nevertheless, her book takes readers on an unforgettable adventure that advances our understanding of this part of the world.

About the author

Thompson’s fascination with Polynesia is personal—she is married to a Polynesian, a Māori from New Zealand. Accordingly, her deep interest in Polynesia is palpable in every chapter. Born in Switzerland and raised in Boston, Thompson graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Dartmouth College. She’s been editor of the prestigious Harvard Review, a literary journal, since 2000. Sea People was published in 2019 by Harper and has received countless honors, among them the 2020 Australian Prime Minister’s Literary Award, the 2020 Victorian Premier’s Literary Award, and the 2019 NSW Premier’s General History Award. She is the recipient of various fellowships, including with the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Australia Council.

Even if you’re not a history buff, you’ll enjoy Sea People. If you’re planning to visit Polynesia, read this book first. Alternatively, download the audio version and listen to it while you are traveling. Sea People (Harper Collins, 2019) is available through Amazon, Apple Books and Scrbd, as well as independent booksellers.

A special note: Thompson will be guest lecturer on a Lindblad/National Georgraphic’s expedition from Tahiti to Easter Island, April 5, 2023.